如果男女在智力水平上没有差别但棋类运动女显著弱于男这是否是对女性的歧视导致的

来自wiki,已经附上所有论文的引用,随便翻译的,看不懂的可以看英文,或者和我说哪里翻译的不对哈,哈哈。不要和我争论,我只是搬运数据:

一般智力研究

Chamorro-Premuzic 等。指出,“g 因子通常与一般智力同义使用,是在各种认知 ('IQ') 测试的因子分析中出现的潜在变量。它们并不完全相同。g是一个指标或度量通用智能;它不是通用智能本身。”

通常用于测量智力的所有或大部分主要测试中,男性和女性之间的总体得分没有差异。因此,男性和女性的平均智商分数几乎没有差异。然而,在数学和语言测量等特定领域,已经报告存在了差异。此外,研究发现男性分数的变异性大于女性分数,导致智商分布顶部和底部的男性多于女性。

在g因子中支持男性或女性使用韦克斯勒成人智力量表(WAIS III 和 WAIS-R)的研究发现,一般智力中,有利男性表明的差异非常小。这在各国是一致的。在美国和加拿大,IQ 分有 2 到 3 分对男性有利,而在中国和日本,IQ 分上升到 4 分对男性有利。相比之下,一些研究发现成年女性有更大的优势。对于美国和荷兰的孩子来说,有1到2个IQ点差异有利于男孩。其他研究发现,女孩在剩余语言因素方面略有优势。

2004年的荟萃分析由理查德·林恩和保罗·欧宁发表在2005年, 发现的男性平均智商超过了女性达5分的的瑞文推理测验考试。Lynn 的发现在Nature的一系列文章中进行了辩论。他认为男性的优势比大多数测试表明的要大,并指出因为女孩比男孩成熟得更快,并且认知能力随着生理年龄而不是日历年龄(with physiological age, rather than with calendar age,)而增加,因此男女差异很小或为负在青春期之前,但男性在青春期后具有优势,并且这种优势会持续到成年期。

赞成没有性别差异或没有决定性的共识大多数研究发现,在一般智力方面,对男性的优势差异很小,或者没有性别差异。2000 年,研究人员Roberto Colom和Francisco J. Abad对 10,475 名成年人进行了一项大型研究,他们进行了五项来自初级心理能力的IQ 测试,发现性别差异可以忽略不计或没有显着差异。进行的测试是词汇、空间旋转、语言流畅性和归纳推理。

由于所使用的测试类型,关于智力性别差异的文献产生了不一致的结果,这导致了研究人员之间的争论。Garcia (2002) 认为一般智力(IQ)可能存在微小的不显着的性别差异,但这可能不一定反映一般智力或g因子的性别差异。尽管大多数研究人员区分了g和 IQ,但那些主张更高男性智力的人断言 IQ 和g是同义词(Lynn & Irwing 2004),因此真正的划分来自于定义与g 相关的IQ因素。2008 年,Lynn 和 Irwing 提出,由于工作记忆能力与g因子的相关性最高,如果发现工作记忆任务存在差异,研究人员将别无选择,只能接受更高的男性智力。因此,Schmidt (2009) 发表的一项神经影像学研究通过测量n-back工作记忆任务的性别差异对该提议进行了调查。结果发现工作记忆容量没有性别差异,因此与 Lynn 和 Irwing (2008) 提出的立场相矛盾,更符合那些认为智力没有性别差异的观点。随后对 Raven 的渐进矩阵数据进行的元分析显示,智力没有性别差异。

研究人员Richard E. Nisbett、Joshua Aronson、Clancy Blair、William Dickens、James Flynn、Diane F. Halpern和Eric Turkheimer 2012 年发表的一篇评论讨论了Arthur Jensen 1998 年关于智力性别差异的研究。Jensen 的测试是显着的 g-loaded 但没有设置来消除任何性别差异(阅读差异项目功能)。他们总结了他的结论,正如他引用的那样:“没有发现 g 平均水平或 g 变异性存在性别差异的证据。平均而言,男性在某些因素上表现出色;女性在其他方面表现出色。” Jensen 得出的关于g不存在总体性别差异的结论得到了研究人员的进一步证实,他们用一组 42 项智力测试分析了这个问题,并没有发现总体性别差异。

尽管大多数测试没有显示出差异,但还是有一些差异。例如,他们发现女性受试者在语言能力方面表现更好,而男性在视觉空间能力方面表现更好。就语言流利度而言,特别发现女性在词汇和阅读理解方面的表现稍好,而在演讲和论文写作方面则明显更高。特别发现男性在空间可视化、空间感知和心理旋转方面表现更好。研究人员随后建议将流体智力和结晶智力等一般模型分为语言、知觉和视觉空间。g 的域;这是因为,当应用这个模型时,女性擅长语言和感知任务,而男性擅长视觉空间任务,从而消除了智商测试中的性别差异。

可变性

主条目:变异性假设

一些研究已经将智商差异的程度确定为男性和女性之间的差异。男性往往在许多特征上表现出更大的变异性;例如,在认知能力测试中同时获得最高分和最低分。

Feingold (1992b) 和 Hedges 和 Nowell (1995) 报告说,尽管平均性别差异很小并且随着时间的推移相对稳定,但男性的测试分数差异通常大于女性。” Feingold“发现男性是在定量推理、空间可视化、拼写和一般知识的测试中,比女性更易变。... Hedges 和 Nowell 更进一步证明,除了在阅读理解、知觉速度和联想记忆测试中的表现外,在高分个体中观察到的男性多于女性。”

大脑和智力两性之间大脑生理学的差异不一定与智力差异有关。虽然男性的大脑更大,但男性和女性的智商相同,智商得分也相同。对于男性,额叶和顶叶的灰质体积与智商相关;对于女性来说,额叶和布洛卡区(用于语言处理)的灰质体积与智商相关。

数学在各个国家和地区,男性在数学考试中的表现优于女性,但数学成绩的男女差异与社会角色中的性别不平等有关。在 2008 年由美国国家科学基金会资助的一项研究中,研究人员表示,“在标准化数学考试中,女孩的表现与男孩一样好。虽然 20 年前,高中男生在数学方面的表现优于女孩,但研究人员发现情况不再如此。他们说,原因很简单:过去,女孩上的高等数学课程比男孩少,但现在她们上的数学课和男孩一样多。”然而,研究表明,虽然男孩和女孩的平均表现相似,但男孩在表现最好和最差的人中所占比例过高。

SAT数学上的一个小的表现差异仍然显示出男性男性优势,尽管差距从 1975 年的 40 分(5.0%)缩小到 2020 年的 18 分(2.3%)。然而, SAT 不是一个具有代表性的样本,因为它只测试即将上大学的学生,而且自 1990 年代以来,上大学的女性多于男性。相反,国际 PISA 考试提供了具有代表性的样本。在 2018 年的数学 PISA 中,参加的76 个国家中有 39.5% 的女孩和男孩的表现没有统计学上的显着差异。同时,在 32 个国家(42.1%)中,男孩的表现优于女孩,而在14 个国家(18.4%)中,女孩的表现优于男孩。平均而言,男孩的表现比女孩高 5 分(1%)。然而,总体而言,社会经济背景相似的男孩和女孩在数学和科学方面的性别差距并不显着。

2008 年发表在《科学》杂志上的一项荟萃分析使用了超过 700 万学生的数据,发现男性和女性的数学能力在统计学上没有显着差异。2011 年的荟萃分析对 1990 年至 2007 年的 242 项研究进行了涉及 1,286,350 人的研究,发现数学成绩没有总体性别差异。荟萃分析还发现,尽管总体上没有差异,但在高中阶段仍然存在在解决复杂问题时有利于男性的微小性别差异。然而,作者指出,男孩继续比女孩上更多的物理课程,这些课程训练复杂的解决能力,并且可能提供比纯数学更强的训练。

研究人员还指出,数学课程表现指标的差异的结果偏向女性。

关于性别不平等,一些心理学家认为,关于数学成绩的许多历史和当前的性别差异可能与男孩比女孩接受数学鼓励的可能性更高有关。过去包括现在有些时候, 父母们仍然更可能将儿子的数学成绩视为一项天生的技能,而女儿的数学成绩更可能被视为她努力学习的目标。这种态度上的差异可能会阻碍女孩和妇女进一步参与与数学相关的学科和职业。

刻板印象威胁已被证明会影响男性和女性的数学表现和信心。

阅读和语言技能研究表明,女性在阅读和语言技能方面具有优势。在国际 PISA 阅读考试中,所有国家/地区的女孩始终优于男孩,并且所有差异均具有统计学意义。在最近的 PISA 考试(2018 年)中,女生比男生高出近 30 分。在经合组织国家,平均有 28% 的男孩没有达到 2 级的阅读水平。

研究表明,女孩花在阅读上的时间比男孩多,阅读更多是为了好玩,这可能是造成差距的原因之一。

空间能力元研究显示男性在心理旋转、评估水平和垂直性方面的优势,以及在空间记忆的大多数方面的男性优势。多项研究表明,在许多与感知方向相关的空间任务中,女性往往比男性更依赖视觉信息。女性对空间记忆的某些组成部分具有优势。男性在细粒度度量位置重建方面表现出选择性优势,强调绝对空间坐标,而女性在空间位置记忆方面表现出优势,即准确记住相对物体位置(物体所在位置)的能力;然而,空间位置记忆的优势很小,而且跨研究不一致。

提出的进化假设是,男性和女性进化出不同的心理能力以适应他们在社会中的不同角色,包括以劳动为基础的角色。例如,“祖先女性更经常在广阔的地理区域内寻找水果、蔬菜和根茎。” 基于劳动的角色解释表明,由于在狩猎期间导航等行为,男性可能已经进化出更大的空间能力。

在物理环境中进行的研究结果并不能确定性别差异。对同一任务的各种研究显示没有差异。有研究表明,在两个地方之间找到一条路没有区别。

心理旋转和类似空间任务的表现受性别期望的影响。例如,研究表明,在测试之前被告知男性通常表现更好,或者该任务与通常与男性相关的航空工程等工作与通常与女性相关的时装设计等工作相关,将产生负面影响影响女性在空间旋转方面的表现,并在受试者被告知相反的情况时对其产生积极影响。

玩电子游戏等体验也会显着提高一个人的心理旋转能力。尤其是玩动作电子游戏,女性的空间能力比男性更能受益,直至消除空间注意力的性别差异。在此背景下研究的动作视频游戏(例如第一人称射击游戏)目前并不受到女性玩家的青睐。

睾酮和其他雄激素作为心理性别差异原因的可能性一直是一个研究课题,但结果喜忧参半。对因先天性肾上腺增生而在子宫内暴露于异常高水平雄激素的女性的荟萃分析得出结论,没有证据表明这些人的空间能力增强。荟萃分析推测,某些空间任务中的平均性别差异可以部分解释为在生命周期的不同时间暴露雄激素,例如在青春期,或者通过男性和女性的不同社会化经历。[58]此外,一项荟萃分析显示,虽然接受睾酮治疗的女性转男性跨性别者确实提高了空间能力,但服用雄激素抑制剂的男性转女性跨性别者的空间能力也有改善或没有恶化。

学术界的性别差异2014 年发表在《心理公报》杂志上的一项关于学业成绩性别差异的元分析发现,在小学、初中/初中、高中以及大学本科和研究生阶段,女性在教师分配的学分中的表现优于男性。新不伦瑞克大学的研究人员 Daniel Voyer 和 Susan D. Voyer 进行的荟萃分析提取了 97 年的 502 个效应量和 1914 年至 2011 年的 369 个样本。

除了学术能力的性别差异之外,最近的研究还关注女性在高等教育中的代表性不足,特别是在自然科学、技术、工程和数学 ( STEM ) 领域。

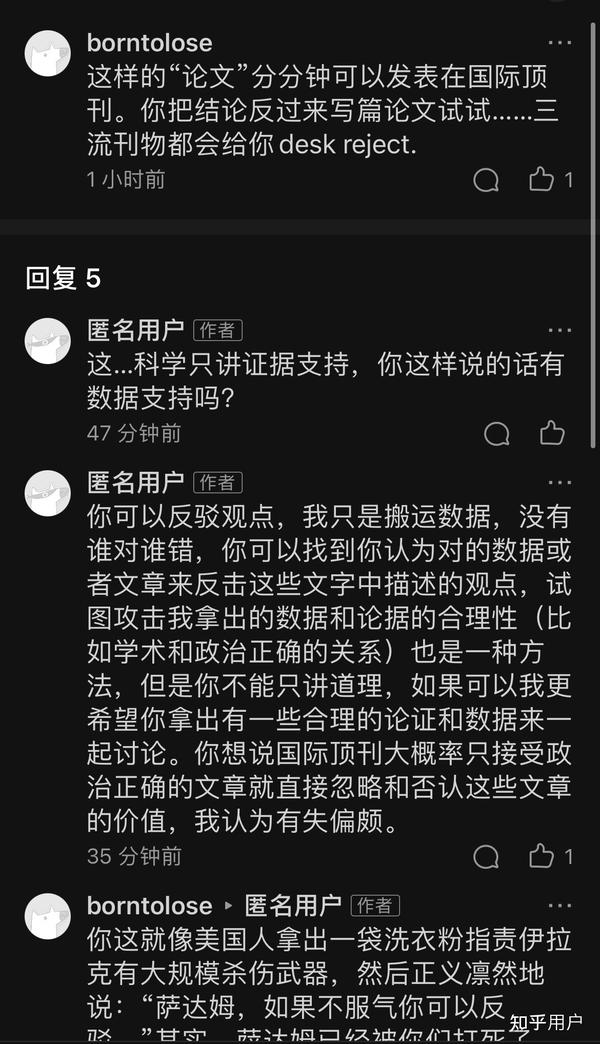

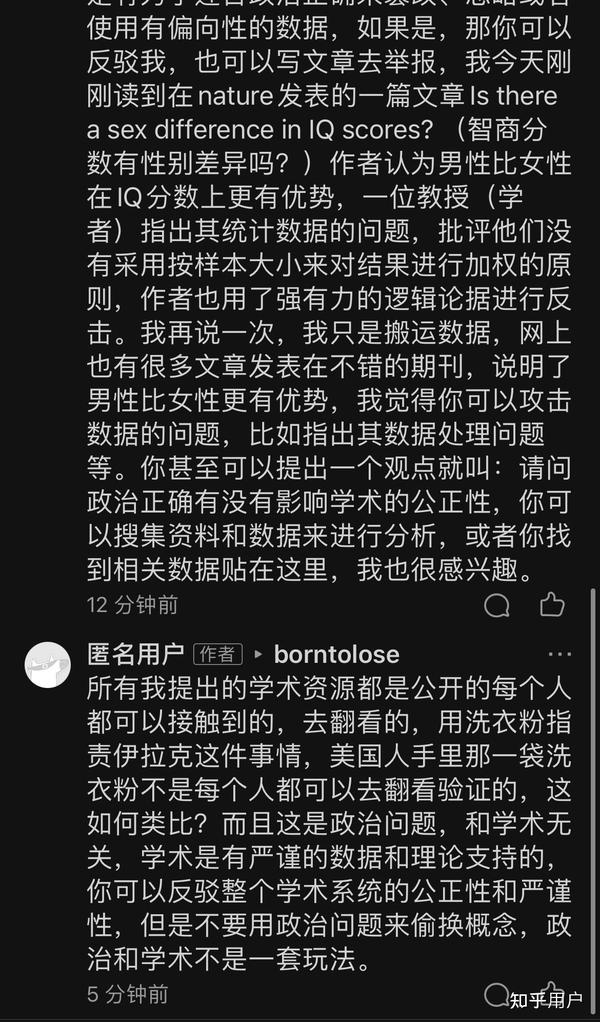

可以评价数据,可以评价观点,可以反驳观点,你们如果想这样偷换概念的回复的话就不要评价,不要和我说什么zz问题,偷换概念,我举例出来的每一篇文章都是有出处,均可查验的,别用美国人手里的洗衣粉来讽刺我,美国人手里的洗衣粉不是每个人都能去看的查验的,我们不知道具体美国人手里拿的是什么才会去质疑,并不是公正公开的;但是我提出的数据是可以查的,不是编造的。不要为了反驳而反驳,反驳观点可以,质疑数据的公正是可以的,网上并不是没有研究文章发出来男性比女性在智商上有优势的说法和数据,大家都可以去看看,我的初衷只是希望能看看有没有真实可靠的数据,样本是相对来说随机和足够大的,这样才有意义,而不是去讨论个人经验和小范围的来源不可靠的个人感觉这类数据,我也说了文章我还没仔细看,我也找到一些其他方面的数据,比如有科学家认为男性比女性在数学和空间方面有一定优势的,但也有科学家反驳这些观点。能不能为了单纯不服气或者单纯为了反驳就扯东扯西,偷换概念。说真的这些朋友要是真的能因为反驳观点去看几篇文章我也觉得我写下这些值得了,如果真的想支持男性比女性在智商或者数学这方面更有天赋,就更应该用实际行动去用数据,或者至少是贴个数据来源明确的文章来表明,而不是用情绪化的思考结果和偷换概念来反驳。

这类人真的不想回复,你真的看完了这篇文章了吗?你真的仔细读了吗?这回答是辩证的,并不是一味的单纯支持女性智商比男性高,就只是说差异不大而已,你不感兴趣你为什么要回答这个问题呢?你为什么来看这个问题呢?你为什么回复我呢?你感兴趣这个话题,不然你不会回复我,你只是没看到你要的答案你就着急了。我也不想一一回复,都是输出情绪,别说我打拳,打拳是打的情绪,是个人经验,我给的是搬运数据,我真的不屑于什么打不打的,我觉得就是谁有理就帮谁,直接怼数据就完事了。如果说男女智力差不多这件事就是打拳,承认男女智力差别不大就是女权,那我觉得挺可笑的。

搬运英文原文:

Background

Chamorro-Premuzic et al. stated, "The g factor, which is often used synonymously with general intelligence, is a latent variable which emerges in a factor analysis of various cognitive ('IQ') tests. They are not exactly the same thing. g is an indicator or measure of general intelligence; it's not general intelligence itself."[15]

All or most of the major tests commonly used to measure intelligence have been constructed so that there are no overall score differences between males and females. Thus, there is little difference between the average IQ scores of men and women.[16][17] Differences have been reported, however, in specific areas such as mathematics and verbal measures.[4][6][5] Also, studies have found the variability of male scores is greater than that of female scores, resulting in more males than females in the top and bottom of the IQ distribution.[6]

In favor of males or females in g factor

Research, using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS III and WAIS-R), that finds general intelligence in favor of males indicates a very small difference.[3] This is consistent across countries.[3] In the United States and Canada, the IQ points range from two to three points in favor of males, while the points rise to four points in favor of males in China and Japan.[3] By contrast, some research finds greater advantage for adult females.[4] For children in the United States and the Netherlands, there are one to two IQ point differences in favor of boys.[3] Other research has found a slight advantage for girls on the residual verbal factor.[3]

A 2004 meta-analysis by Richard Lynn and Paul Irwing published in 2005 found that the mean IQ of men exceeded that of women by up to 5 points on the Raven's Progressive Matrices test.[18][19] Lynn's findings were debated in a series of articles for Nature.[20] He argued that there is a greater male advantage than most tests indicate, stating that because girls mature faster than boys, and that cognitive competence increases with physiological age, rather than with calendar age, the male-female difference is small or negative prior to puberty, but males have an advantage after adolescence and this advantage continues into adulthood.[3]

In favor of no sex differences or inconclusive consensus

Most studies find either a very small difference in favor of males or no sex difference with regard to general intelligence.[3][21] In 2000, researchers Roberto Colom and Francisco J. Abad conducted a large study of 10,475 adults on five IQ tests taken from the Primary Mental Abilities and found negligible or no significant sex differences. The tests conducted were on vocabulary, spatial rotation, verbal fluency and inductive reasoning.[21]

The literature on sex differences in intelligence has produced inconsistent results due to the type of testing used, and this has resulted in debate among researchers.[15] Garcia (2002) argues that there might be a small insignificant sex difference in intelligence in general (IQ) but this may not necessarily reflect a sex difference in general intelligence or g factor.[15] Although most researchers distinguish between g and IQ, those that argued for greater male intelligence asserted that IQ and g are synonymous (Lynn & Irwing 2004) and so the real division comes from defining IQ in relation to g factor. In 2008 Lynn and Irwing proposed that since working memory ability correlates highest with g factor, researchers would have no choice but to accept greater male intelligence if differences on working memory tasks are found. As a result, a neuroimaging study published by Schmidt (2009) conducted an investigation into this proposal by measuring sex differences on an n-back working memory task. The results found no sex difference in working memory capacity, thus contradicting the position put forward by Lynn and Irwing (2008) and more in line with those arguing for no sex differences in intelligence.[15] A later meta analysis of Raven's Progressive Matrices data featuring large, international datasets revealed no sex differences in performance.[22][23]

A 2012 review by researchers Richard E. Nisbett, Joshua Aronson, Clancy Blair, William Dickens, James Flynn, Diane F. Halpern and Eric Turkheimer discussed Arthur Jensen's 1998 studies on sex differences in intelligence. Jensen's tests were significantly g-loaded but were not set up to get rid of any sex differences (read differential item functioning). They summarized his conclusions as he quoted, "No evidence was found for sex differences in the mean level of g or in the variability of g. Males, on average, excel on some factors; females on others." Jensen's conclusion that no overall sex differences existed for g has been reinforced by researchers who analyzed this issue with a battery of 42 mental ability tests and found no overall sex difference.[24]

Although most of the tests showed no difference, there were some that did. For example, they found female subjects performed better on verbal abilities while males performed better on visuospatial abilities.[24] For verbal fluency, females have been specifically found to perform slightly better in vocabulary and reading comprehension and significantly higher in speech production and essay writing.[25] Males have been specifically found to perform better on spatial visualization, spatial perception, and mental rotation.[25] Researchers had then recommended that general models such as fluid and crystallized intelligence be divided into verbal, perceptual and visuospatial domains of g; this is because, as this model is applied, females excel at verbal and perceptual tasks while males excel on visuospatial tasks, thus evening out the sex differences on IQ tests.[24]

Variability

Main article: Variability hypothesis

Some studies have identified the degree of IQ variance as a difference between males and females. Males tend to show greater variability on many traits; for example having both highest and lowest scores on tests of cognitive abilities.[6][5]

Feingold (1992b) and Hedges and Nowell (1995) have reported that, despite average sex differences being small and relatively stable over time, test score variances of males were generally larger than those of females."[26] Feingold "found that males were more variable than females on tests of quantitative reasoning, spatial visualisation, spelling, and general knowledge. ... Hedges and Nowell go one step further and demonstrate that, with the exception of performance on tests of reading comprehension, perceptual speed, and associative memory, more males than females were observed among high-scoring individuals."[26]

Brain and intelligence

See also: Neuroscience of sex differences

Differences in brain physiology between sexes do not necessarily relate to differences in intellect. Although men have larger brains, men and women have equal IQs and are equal in IQ scores.[27] For men, the gray matter volume in the frontal and parietal lobes correlates with IQ; for women, the gray matter volume in the frontal lobe and Broca's area (which is used in language processing) correlates with IQ.[28]

Women have greater cortical thickness, cortical complexity and cortical surface area (controlling for body size) which compensates for smaller brain size.[29] Meta-analysis and studies have found that brain size explains 6–12% of variance among individual intelligence and cortical thickness explains 5%.[30]

Mathematics performance

Across countries, males have performed better on mathematics tests than females, but the male-female difference in math scores is related to gender inequality in social roles.[31] In a 2008 study paid for by the National Science Foundation in the United States, researchers stated that "girls perform as well as boys on standardized math tests. Although 20 years ago, high school boys performed better than girls in math, the researchers found that is no longer the case. The reason, they said, is simple: Girls used to take fewer advanced math courses than boys, but now they are taking just as many."[32][33] However, the study indicated that, while boys and girls performed similarly on average, boys were over-represented among the very best performers as well as among the very worst.[34]

A small performance difference in mathematics on the SAT[35] persists in favor of males, though the gap has shrunk from 40 points (5.0%) in 1975[36] to 18 points (2.3%) in 2020.[37] However, the SAT is not a representative sample, given that it tests only college-bound students, and more women than men have attended college since the 1990s.[38] Conversely, the international PISA exam provides representative samples. On the 2018 math PISA, there was no statistically significant difference between the performances of girls and boys in 39.5% of the 76 countries that participated. Meanwhile, boys outperformed girls in 32 countries (42.1%), while girls outperformed boys in 14 (18.4%).[39] On average, boys performed 5 points (1%) higher than girls. However, overall, the gender gap in math and science for boys and girls from similar socio-economic backgrounds was not significant.[39]

A 2008 meta-analysis published in Science using data from over 7 million students found no statistically significant differences between the mathematical capabilities of males and females.[40] A 2011 meta-analysis with 242 studies from 1990 to 2007 involving 1,286,350 people found no overall sex difference of performance in mathematics. The meta-analysis also found that although there were no overall differences, a small sex difference that favored males in complex problem solving was still present in high school. However, the authors note that boys continue to take more physics courses than girls, which train complex solving abilities and may provide stronger training than pure mathematics.[41]

Researchers also note that differences in mathematics course performance measures favor females.[42]

With regard to gender inequality, some psychologists believe that many historical and current sex differences in mathematics performance may be related to boys' higher likelihood of receiving math encouragement than girls. Parents were, and sometimes still are, more likely to consider a son's mathematical achievement as being a natural skill while a daughter's mathematical achievement is more likely to be seen as something she studied hard for.[43] This difference in attitude may contribute to girls and women being discouraged from further involvement in mathematics-related subjects and careers.[43]

Stereotype threat has been shown to affect performance and confidence in mathematics of both males and females.[10][42]

Reading and verbal skills

Studies have shown a female advantage in reading and verbal skills.[2] On the international PISA reading exam, girls consistently outperform boys across all countries, and all differences are statistically significant. In the most recent PISA exam (2018), girls outperformed boys by almost 30 points.[44] On average in OECD countries, 28% of boys did not obtain a reading proficiency level of 2.

Studies have shown that girls spend more time reading than boys and read more for fun, likely contributing to the gap.[45]

Spatial ability

Meta-studies show a male advantage in mental rotation, assessing horizontality and verticality, and a male advantage for most aspects of spatial memory.[46][47][48] A number of studies have shown that women tend to rely more on visual information than men in a number of spatial tasks related to perceived orientation.[49] Women have an advantage for certain components of spatial memory. Whereas men show a selective advantage for fine-grained metric positional reconstruction, where absolute spatial coordinates are emphasized, women show an advantage in spatial location memory, which is the ability to accurately remember relative object positions (where objects are);[47][50][51] however, the advantage in spatial location memory is small and inconsistent across studies.[51]

A proposed evolutionary hypothesis is that men and women evolved different mental abilities to adapt to their different roles, including labor-based roles, in society.[51][52] For example, "ancestral women more often foraged for fruits, vegetables, and roots over large geographic regions."[51] The labor-based role explanation suggests that men may have evolved greater spatial abilities as a result of behaviors such as navigating during a hunt.[53]

Results from studies conducted in the physical environment are not conclusive about sex differences. Various studies on the same task show no differences. There are studies that show no difference in finding one's way between two places.[54]

Performance in mental rotation and similar spatial tasks is affected by gender expectations.[10][55] For example, studies show that being told before the test that men typically perform better, or that the task is linked with jobs like aviation engineering typically associated with men versus jobs like fashion design typically associated with women, will negatively affect female performance on spatial rotation and positively influence it when subjects are told the opposite.[56]

Experiences such as playing video games also significantly increase a person's mental rotation ability.[54] Playing action video games in particular benefits spatial abilities in women more than in men, up to a point where gender differences in spatial attention are eliminated.[57] The action video games (e.g. First-person shooters) studied in this context are currently not preferred by female players.[citation needed]

The possibility of testosterone and other androgens as a cause of sex differences in psychology has been a subject of study, but results have been mixed. A meta-analysis of women who were exposed to unusually high levels of androgens in the womb due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia concluded that there is no evidence of enhanced spatial ability among these individuals.[58] The meta-analysis speculates that average sex differences in some spatial tasks could be partially explained by androgen exposure at a different time of the life span, such as during mini-puberty, or by the different socialization males and females experience.[58] In addition, a meta-analysis showed that, although female-to-male transgender individuals who received testosterone therapy did improve their spatial abilities, male-to-female transgender individuals who took androgen-suppressants also showed an improvement or no deterioration of spatial skills.[59]

Sex differences in academics

A 2014 meta-analysis of sex differences in scholastic achievement published in the journal of Psychological Bulletin found females outperformed males in teacher-assigned school marks throughout elementary, junior/middle, high school and at both undergraduate and graduate university level.[60] The meta-analysis, done by researchers Daniel Voyer and Susan D. Voyer from the University of New Brunswick, drew from 97 years of 502 effect sizes and 369 samples stemming from the year 1914 to 2011.[60]

Beyond sex differences in academic ability, recent research has also been focusing on women's underrepresentation in higher education, especially in the fields of natural science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).[61]

Hunt, Earl B. (2010). Human Intelligence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 378–379. ISBN 978-1139495110.

Mackintosh N (2011). IQ and Human Intelligence. OUP Oxford. pp. 362–363. ISBN 978-0199585595.

Terry WS (2015). Learning and Memory: Basic Principles, Processes, and Procedures, Fourth Edition. Psychology Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-1317350873.

Chrisler JC, McCreary DR (2010). Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology: Volume 1: Gender Research in General and Experimental Psychology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 302. ISBN 978-1441914651.

Lips, Hilary M. (1997). Sex & Gender: An Introduction (3rd ed.). Mountain View, Calif.: Mayfield. p. 40. ISBN 978-1559346306.

Denmark, Florence L.; Paludi, Michele A. (2008). Psychology of Women: A Handbook of Issues and Theories (2nd ed.). Westport, Conn.: Praeger. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-0275991623.

Worell J (2001). Encyclopedia of Women and Gender, Two-Volume Set: Sex Similarities and Differences and the Impact of Society on Gender. Academic Press. p. 441. ISBN 0122272455.

Fine C (2005). Delusions of Gender: The Real Science Behind Sex Differences. Icon Books. p. 96. ISBN 1848313969.

Margarete Grandner, Austrian women in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: cross-disciplinary perspectives, Berghahn Books, 1996, ISBN 1-57181-045-5, ISBN 978-1-57181-045-8

Burt, C. L.; Moore, R. C. (1912). "The mental differences between the sexes". Journal of Experimental Pedagogy. 1 (273–284): 355–388.

Terman, Lewis M. (1916). The measurement of intelligence: an explanation of and a complete guide for the use of the Stanford revision and extension of the Binet-Simon intelligence scale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 68–72. OCLC 186102.

Dennis W (1972). Historical readings in developmental psychology. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 214. ISBN 9780390262998.

Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas; Stumm, Sophie von; Furnham, Adrian (2011). The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences. John Wiley & Sons. p. 416. ISBN 978-1444343113.

Worell J (2001). Encyclopedia of Women and Gender, Two-Volume Set: Sex Similarities and Differences and the Impact of Society on Gender. Academic Press. p. 964. ISBN 0122272455.

Child D (2007). Psychology and the teacher. Continuum. p. 305. ISBN 978-0826487155.

Irwing, Paul; Lynn, Richard (2005). "Sex differences in means and variability on the progressive matrices in university students: A meta-analysis". British Journal of Psychology. 96 (4): 505–24. doi:10.1348/000712605X53542. PMID 16248939. S2CID 14005582.

Lynn, Richard; Irwing, Paul (2004). "Sex differences on the progressive matrices: A meta-analysis". Intelligence. 32 (5): 481–498. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2004.06.008.

Child D (2006). The Psychologist. British Psychological Society. p. 10.[full citation needed]

The Scientific Study of General Intelligence. 2003. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-043793-4.X5033-8. ISBN 9780080437934.

Ceci, Stephen J.; Williams, Wendy M.; Barnett, Susan M. (2009). "Women's underrepresentation in science: Sociocultural and biological considerations". Psychological Bulletin. 135 (2): 218–261. doi:10.1037/a0014412. PMID 19254079.

Brouwers, Symen A.; Van de Vijver, Fons J.R.; Van Hemert, Dianne A. (September 2009). "Variation in Raven's Progressive Matrices scores across time and place" (PDF). Learning and Individual Differences. 19 (3): 330–338. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.10.006.

Nisbett, Richard E.; Aronson, Joshua; Blair, Clancy; Dickens, William; Flynn, James; Halpern, Diane F.; Turkheimer, Eric (February 2012). "Intelligence: New findings and theoretical developments". American Psychologist. 67 (2): 130–159. doi:10.1037/a0026699. PMID 22233090.

Hyde, Janet Shibley (2006). "Women in Science and Mathematics: Gender Similarities in Abilities and Sociocultural Forces". Biological, Social, and Organizational Components of Success for Women in Academic Science and Engineering: Report of a Workshop. National Academies Press. pp. 127–137. ISBN 978-0-309-10041-0.

Archer, John; Lloyd, Barbara (2002-07-11). Sex and Gender. Cambridge University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 9780521635332.

Kalat JW (2012). Biological Psychology. Cengage Learning. pp. 118, 120. ISBN 978-1111831004.

Garrett B, Hough G (2017). Brain & Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Neuroscience. Sage Publications. p. 118. ISBN 978-1506349190.

Sex difference in the human brain, their underpinnings and implications. Elsevier. 2010. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9780444536310.

Pietschnig, Jakob; Penke, Lars; Wicherts, Jelte M.; Zeiler, Michael; Voracek, Martin (2015-10-01). "Meta-analysis of associations between human brain volume and intelligence differences: How strong are they and what do they mean?". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 57: 411–432. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.017. PMID 26449760. S2CID 23180321.

Sternberg RJ, Kaufman SB (2011). The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press. p. 877. ISBN 978-1111831004.

Lewin, Tamar (July 25, 2008)."Math Scores Show No Gap for Girls, Study Finds", The New York Times.

Crooks RL, Baur K (2016). Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. p. 125. ISBN 978-1305887428.

Winstein, Keith J. (July 25, 2008). "Boys' Math Scores Hit Highs and Lows", The Wall Street Journal (New York).

"Gender differences in mathematics performance", p.196. OECD 2015.

Burton, Nancy W.; Lewis, Charles; Robertson, Nancy (December 1988). "SEX DIFFERENCES IN SAT® SCORES". ETS Research Report Series. 1988 (2): i–23. doi:10.1002/j.2330-8516.1988.tb00314.x. ISSN 2330-8516.

"2021 SAT Suite of Assessments Program Results – The College Board". College Board Program Results. 2021-09-08. Retrieved 2021-09-16.

Stoet, Gijsbert; Geary, David C. (2020-06-23). "Gender differences in the pathways to higher education". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (25): 14073–14076.

"Home". Site homepage. Retrieved 2021-09-16.

"Study: No gender differences in math performance". News from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 2021-09-16.

Lindberg, Sara M.; Hyde, Janet Shibley; Petersen, Jennifer L.; Linn, Marcia C. (2010). "New trends in gender and mathematics performance: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 136 (6): 1123–1135. doi:10.1037/a0021276. PMC 3057475. PMID 21038941.

Ann M. Gallagher, James C. Kaufman, Gender differences in mathematics: an integrative psychological approach, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-82605-5, ISBN 978-0-521-82605-1[page needed]

Wood, Samuel; Wood, Ellen; Boyd Denise (2004). "World of Psychology, The (Fifth Edition)", Allyn & Bacon ISBN 0-205-36137-4.[page needed]

"PISA 2018 Data". PISA 2018 Results (Volume II). 2019-12-03. doi:10.1787/fb6da32e-en. ISSN 1996-3777.

Hughes-Hassell, Sandra; Rodge, Pradnya (2007). "The Leisure Reading Habits of Urban Adolescents". Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 51 (1): 22–33. ISSN 1081-3004.

Fernandez-Baizan, C.; Arias, J.L.; Mendez, M. (February 2019). "Spatial memory in young adults: Gender differences in egocentric and allocentric performance". Behavioural Brain Research. 359: 694–700. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2018.09.017. hdl:10651/49938. PMID 30273614. S2CID 52879258.

Voyer, Daniel; Voyer, Susan D.; Saint-Aubin, Jean (April 2017). "Sex differences in visual-spatial working memory: A meta-analysis". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 24 (2): 307–334. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1085-7. PMID 27357955. All the tasks produced a male advantage, except for memory for location, where a female advantage emerged.

Chrisler, Joan C; Donald R. McCreary (2010). Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology. Springer. p. 265. ISBN 9781441914644.

Witkin, Herman A; Murphy, Gardner; Lewis, H. B; Hertzman, Max; Machover, Karen; Bretnall Meissner, P; Wapner, Seymour (1954). Personality through perception: an experimental and clinical study. Harper. OCLC 1111741689.[page needed]

Becker, Jill B.; Berkley, Karen J.; Geary, Nori; Hampson, Elizabeth; Herman, James P.; Young, Elizabeth (2007). Sex Differences in the Brain: From Genes to Behavior. Oxford University Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0198042556.

Bosson, Jennifer K.; Buckner, Camille E.; Vandello, Joseph A. (2021). The Psychology of Sex and Gender. SAGE Publications. p. 271. ISBN 978-1544394039.

Eals, Marion; Silverman, Irwin (1992). "Sex differences in spatial abilities: evolutionary theory and data". In Barkow, J. H.; Cosmides, L.; Tooby, J. (eds.). The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 533–549.

Geary, David C. (1998). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences. American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-55798-527-9.[page needed]

Devlin, Ann Sloan, Mind and maze: spatial cognition and environmental behavior, Praeger, 2001, ISBN 0-275-96784-0, ISBN 978-0-275-96784-0[page needed]

Paula J. Caplan, Gender differences in human cognition, Oxford University Press US, 1997, ISBN 0-19-511291-1, ISBN 978-0-19-511291-7[page needed]

Newcombe, Nora S. (2007). "Taking Science Seriously: Straight Thinking About Spatial Sex Differences". Why aren't more women in science?: Top researchers debate the evidence. pp. 69–77. doi:10.1037/11546-006. ISBN 978-1-59147-485-2.

Spence, Ian, Feng, Jing, Video Games and Spatial Cognition, Review of General Psychology, 2010,[page needed]

Collaer, Marcia L.; Hines, Melissa (February 2020). "No Evidence for Enhancement of Spatial Ability with Elevated Prenatal Androgen Exposure in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Meta-Analysis". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 49 (2): 395–411. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01645-7. PMID 32052211. S2CID 211101661.

Karalexi, Maria A.; Georgakis, Marios K.; Dimitriou, Nikolaos G.; Vichos, Theodoros; Katsimpris, Andreas; Petridou, Eleni Th.; Papadopoulos, Fotios C. (September 2020). "Gender-affirming hormone treatment and cognitive function in transgender young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 119: 104721. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104721. PMID 32512250. S2CID 219123865.

Voyer, Daniel; Voyer, Susan D. (2014). "Gender differences in scholastic achievement: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 140 (4): 1174–1204. doi:10.1037/a0036620. PMID 24773502.

S. J. Ceci, W. M. Williams, Why Aren’t More Women in Science? (APA Books, Washington, DC, 2007)[page needed]

另外的网友对于在杭州哪里买麻将机比较好这个话题也是给了不同的答案,人家说去京东买比去某宝买好。为什么会这么说,这关键的原因还是因为如果在京东买麻将机的话,商品质量保证还是多一点。而且,对于京东来说人家是只要你下单,在48小时之内到家给你安装的。所以说,小编还是觉得在京东上买比较放心。小编别的不多说,手指头那么轻轻一点就在京东上面下了一单。

很多人可能会说了,我这个人运气好,玩杭州麻将杠的时候一直顺风顺水,怎么打都赢啊,其实这里面也有着很大的陷阱,一旦你被胜利冲昏了头脑,不加思考就扔牌,那反而会阴沟里面翻船,注意好自己的心态,是极为重要的一点,同时在杭州麻将杠游戏里面遇上僵局应该是大家最不乐意看到的,一局牌摸了一轮又一轮,就是没法结束,也非常地让人疲倦,这时候需要注意的就是不要麻木,一定要随时保持警惕,对于对手是否换了听的牌一定要及时跟进,避免自己不小心点炮。